Powers of a permutation matrix - Part 1

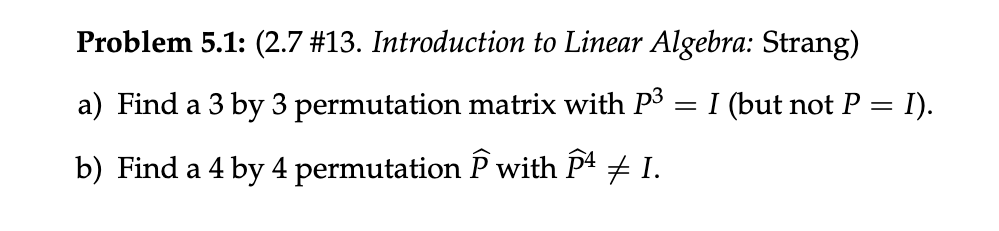

Published on 21 Sep 2023, under:I came across this problem while working through the MITOCW course on Linear Algebra. The lectures are interesting in of themselves, but I got completely sidetracked when I started on this problem:

This got me wondering if, given a permutation matrix P, we’d always be able to find a k, such that Pk = I, where I is the identity matrix. Equivalently, I wondered if, given a permutation of n objects, one can always recover the initial arrangement by successfully performing the same permutation over and over again. That is, if there is always a k, such that pk = e (where e is the identity, a permutation that leaves the arrangement of objects unchanged) for a given permutation p.

It turns out that the answer is that there is! Given any permutation of n objects, you can recover the original arrangement by performing the same permutation on the object a specific number of times. The minimum number of times the permutation is to be repeated for a given permutation, depends on the internal structure of the permutation.

To prove this, we have to first recognize that every permutation has atleast one cycle. A cycle is a permutation such that if you start with one element and track its position as the permutation is repeatedly applied, it eventually returns to its original position. As an example consider this simple collection of four objects ( a, b, c, d ). If we apply the following permutation: a -> b, b -> c, c -> d, and d -> a (call this permutation p), and track the position of c, we have ( d, a, b, c ). Applying the permutation again, i.e., p2, we get ( c, d, a, b ). One more application (p3) gets us to ( b, c, d, a ), and finally p4 gives ( a, b, c, d ) and we see that c, as well as the other elements, has returned to its starting position.

So why is it true that a permutation will have atleast one cycle? To understand this, consider a permutation on n objects where a subset of the objects have changed positions. If no elements have changed position, then each element can thought of as being in a cycle of size 1. If more than one object has changed positions after the permutation has been applied, any one object in the subset will have moved to the position occupied by another object which will in turn have moved to a different position. For a finite subset of objects, this means that the position occupied by the initial object will now be occupied by a different object in the subset. If we suppose that this permutation does not have a cycle, it implies that the first object will never return to it’s orginal position no matter how many times the permutation is applied. This can only happen if the first object never reaches the position of the last object (which moves to the first position upon first application of the permutation). But this can only happen if the first object never reaches the position of the second-to-last object, as so on, until we are forced to conclude that the first object can never even reach the second position, implying that it did not move. This contradicts the statement that all objects in the subset changed positions. So the only way out is to admit that this the subset is in a cycle and that the size of the cycle is the number of elements in the subset.

In Part 2, we will explore some specific permutations that are composed of simple cycles, and see what happens when the permuation is applied repeatedly to a set of objects.