Implementing TCP in Rust - Part 2

Published on 16 Apr 2022, under:In my last post on @jonhoo’s live stream on implementing TCP in Rust, I covered everything upto the point where we parsed the source IP address, destination IP address, and payload length from the packet we received from a remote host. We emulated a remote host using a virtual interface, tun0, which we created using the TUN/TAP universal device driver. Picking up where we left off, in this post we explore the packet we received further, parse the TCP segment, and respond to the packet in a particular way, as is specified in RFC 793, the TCP functional specification document.

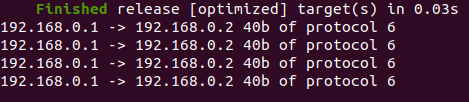

As we are trying to implement TCP, we can try to make a TCP connection using netcat to any port:

nc 198.168.0.2 80

We see that 40 bytes are received of protocol 6, which is TCP.

Now that we have TCP packets, we can dive deeper into it, and go about actually implementing TCP. A good place to start that is RFC 793, which specifies the protocol in great detail. As an aside, it had never occurred to me to ask what it means to implement something like TCP. It simply means implement the expected behavior and rules as specified in the Standards document. For example, if the document says that a host (let’s say a server) that receives a SYN packet (which is a type of TCP segment, something we will go into detail in the next couple of posts) from a remote host (client), the server has to respond in a way that is specified in RFC 793. In the case of the SYN packet, the server can respond to the packet by either sending an ACK plus a SYN of it’s own, or choose to close the connection.

To parse the TCP packets, we can use etherparse again. Another option is to write methods to parse the packets as well, but since most of the implementation of TCP has to do with bit manipulation, and not parsing, it is more convenient to let etherparse do all the heavy lifting here. With that out of the way, we can start with the actual details of the implementation. To begin with, there are two key objects we have to keep track of: the connection, which is identified by the source ip address, the source port, the destination ip address, and the destination port; and the state of the connection which can be either Listening, Closed, or Established, among others. The entire list of states can be found in RFC 793. We can store the the quad of values in the connection, and the state of the connection in structs, and have a hashmap from the quad to the state to hold all the connections.

#[derive(Clone, Copy, Debug, Hash, Eq, PartialEq)]

struct Quad { // This struct identifies each connection

src: (Ipv4Addr, u16), // (<ip_addr>, <port>)

dst: (Ipv4Addr, u16),

}

enum State { // enum to hold connection state value

// Listen,

SynRcvd,

Estab,

FinWait1,

FinWait2,

TimeWait,

}

pub struct Connection { // struct to hold the state of a particular connection [src ip, src port, dest ip, dest src]

state: State,

send: SendSequenceSpace,

recv: RecvSequenceSpace,

ip: etherparse::Ipv4Header,

tcp: etherparse::TcpHeader,

}

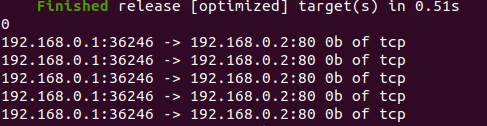

The first thing to do when we receive a TCP segment is to make a connections entry for it. We store the src ip, src port, dest ip, and dest port in an instance of the Quad struct above, and check the hashmap if an entry exists for the connection. If one exists already, we have to deal with the packet. We implement this in a function called on_packet(). If there isn’t an entry in the hashmap for the connection, it is a new connection, and we will implement this functionality in a function called accept(). For now, we just print the quad values. When we run it now, we see all the data, and 0b of payload which indicates that it’s header only.

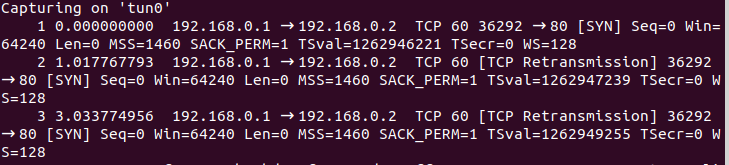

To see exactly what the the packet we received looks like, we can run tshark again and then start a TCP connection.

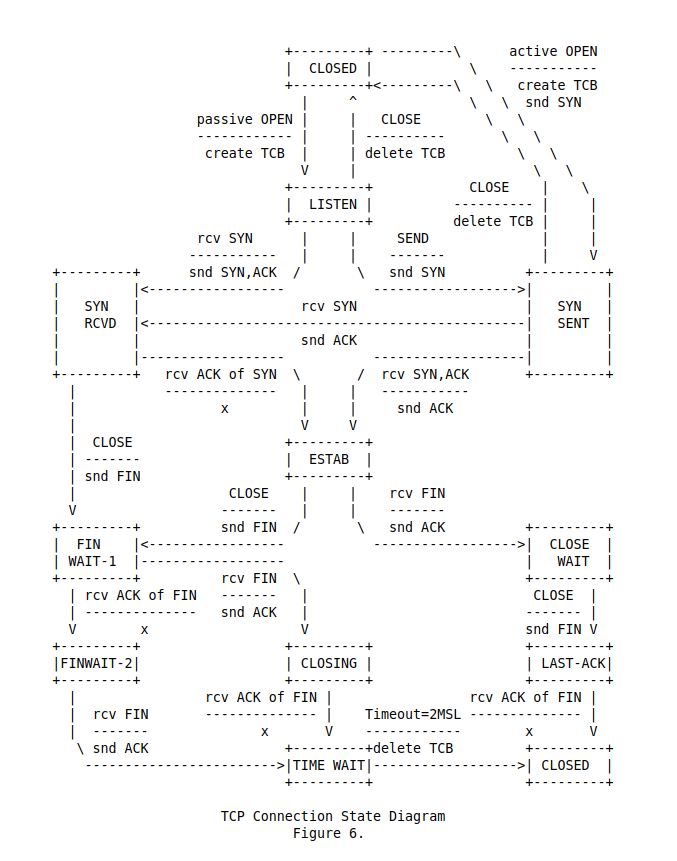

We can see that the first packet we received was a SYN packet. Having received it, we have to decide how we should respond. To do this, we can refer to RFC 793 and see what is to be done next. The entire process flow can be summarized in the following diagram:

A connection can be in CLOSED: meaning we do not reply if we are sent a packet, or LISTEN, meaning if someone we are not speaking to atm, sends a packet we are always going to deal with that packet. In our implementation we are going to assume that every port is listening. Exploring the diagram a bit, we see that if someone sends us a SYN, we can either close the connection, or we can send an ACK and a SYN ourself. I.e., we acknowledge the SYN that was sent, and send a SYN of our own asking if the remote machine wants to establish a connection. If we receive an ACK for our SYN, the connection is then established. If we wish to establish a connection, we start of at CLOSED, from where we go to OPEN, and then send a SYN. If the remote machine sends a SYN and ACK, we send an ACK and the connection is established. In our implementation, we implement the server part first, and the client part later. Since we are in server mode, we never send out any packets first.

If a SYN packet is received, we need to handle that and start establishing a connection. Basically we have to write a TCP header. We can use etherparse again for this, which has a new() method to create a TCP segment. it takes a source port, destination port, sequence number and window size. We already know that source port for our TCP header is the destination port from the received SYN packet, and the destination port is the source port from the same packet. Sequence number and window size are something we have to figure out. As we are now responding to the SYN received from remote host, we have to send SYN and ACK, so we have to set those two bits in the header. This will have to be wrapped in an ipv4 header to send it back to the remote host. Again we can use etherparse to create the header for us (with new), and this takes payload length which is equal to length of the SYN/ACK msg, the timeout set to 64, the protocol, in this case TCP, source and destination addresses. Once done, this packet will now have to be sent out.

I will stop here for this post. In my next post I will cover the part of the live stream that talks about writing TCP segments and IP packets, what fields are to be written, how they are calculated, and finally how to send them out to the “remote host” (the client, in this implementation).