Implementing TCP in Rust

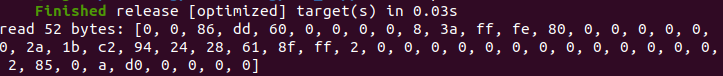

Published on 25 Mar 2022, under:One good thing about TwitterTM is that once in a while I come across a tweet that voices out load the exact thing I was looking for. In this instance, I found this tweet from @b0rk, looking for networking courses. There were a lot of good suggestions, but this one caught my eye: Implementing TCP, by @jonhoo. It is an implementation of TCP using Rust. It drew my eye immediately as learning Rust has been on my mind for a while now. Now, I do not know the first thing about Rust, and not very much more about networking, but I have found that I learn best by doing, so I drove right into it. Jon mentions RFC 1180 as a good tutorial to TCP/IP which I started reading in parallel to the video series. I’m about 45 minutes into Part 1, and there are already a bunch of concepts with which I am completely unfamiliar. Nevertheless, just by following along, I was able to write a “virtual” NIC in rust. The only thing it does is read an IP packet as a bunch of bytes. Still, pretty cool. It wasn’t without hicups though. The setcap command did not work until I provided the entire path to the compiled binary, and for some reason $CARGO_TARGET_DIR, which I assumed was set during the setup, was not really set to anything. But barring these minor setbacks, the code compiled and ran pretty well.

The first new rust concept i hit upon in the video was cargo. Cargo is the build and packaging system of Rust. I learned that it downloads the necessary libraries and builds your code. You list your projects dependencies (packages of code, called Crates) in the .toml file, and Cargo will download and link them for you. You can use cargo to build your code using “cargo build –release” and it will build and create your binaries in a separate folder. There are a bunch of options you can specify in the build command like ‘r’ to build your code, and then run it, or ‘b’ to only compile your code and build the binary.

The tutorial introduced TUN/TAP next. This is a really cool kernel module that provides packet transmission and reception for User space programs. If I understand correctly, it creates a virtual network adapter to whom the kernel forwards packets from a user space program, and whose packets the kernel sends to the user space program. There is already a Rust crate for Tun/Tap bindings which is used in the tutorial. It’s a really cool module, and I’m sure I’ll be using it a lot in my networking adventures in the future. The actual syntax is very similar to C and Jon quickly covered the actual code by following the tun_tap docs closely.

use std::io;

fn main() -> io::Result<()> {

let nic = tun_tap::Iface::new("tun0", tun_tap::Mode::Tun)?;

let mut buf = [0u8; 1504];

let nbytes = nic.recv(&mut buf[..])?;

eprintln!("read {} bytes: {:x?}", nbytes, &buf[..nbytes]);

Ok(())

}

A new thing in Rust is the syntax to use library functions. For example, to user a function called “some_function()” that is part of “some_library”, you would write: some_library::some_function(). A few other new things are “match”, OK(), Err(), and the “->” and “=>” operators, but I will dive deeper into them as I move forward.

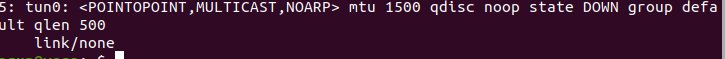

To use TUN/TAP, we need CAP_NET_ADMIN privileges which is confirgured with the setcap command: sudo setcap cap_net_admin=eip <path_to_target>. The tutorial uses $CARGO_TARGET_DIR in the path, but for some reason this did not work for me. I am not really sure if I have to set this variable myself, or if it gets set by cargo. In any case I was able to get around this by simply providing the relative path to the target. Finally, we compiled the code and ran it. Now when you run ip addr, you can see tun0 show up in your list of network devices.

As of now, tun0 is not really doing anything. To configure it to listen for IP packets we have to run the following commands:

sudo ip addr add <some IP address> dev tun0

sudo ip link set up dev tun0

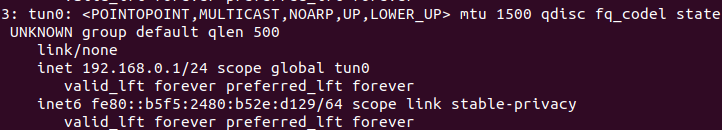

"ip addr add <static IP address> dev <device name>" adds an ip address to the newly created network device tun0, and once that’s done, we bring tun0 online with "ip link set up dev <device name>". tun0 will now listen for IP packets and the code will display the bytes in the packet that tun0 received.

To simplify the whole process, all the individual commands were wrapped up in a shell file:

<#!/bin/bash

cargo b --release

sudo setcap cap_net_admin=eip <path to binary>

<path to binary> &

pid=$!

sudo ip addr add 192.168.0.1/24 dev tun0

sudo ip link set up dev tun0

trap "kill $pid" INT TERM

wait $pid

and anytime we want trust to listen for IP packets sent to tun0, we can run the .sh file to compile any changes to the code, set cap_net_admin, run the program, and bring tun0 online.

So now we can bring tun0 online and listen for packets, but the program will stop running once tun0 receives an IP packet. To keep tun0 listening indefinitely, we put it in a loop. Loop is a rust functionality that let’s you run an infinite loop. Just put your code in a block like so

loop {

# code goes here

}

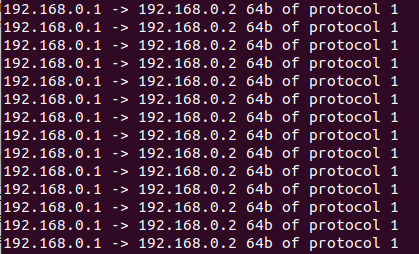

Now we can ping the IP address we set earlier, and the component bytes will be displayed consecutively. However, these bytes are not really readable to most of us, I would imagine. To make better sense of the data, a rust crate called etherparse can be used to parse the hex data and extract useful information from them. We choose to pull source IP, destination IP, payload length, and IP protocol.

match etherparse::Ipv4HeaderSlice::from_slice(&buf[4..nbytes]) {

Ok(p) => {

let src = p.source_addr();

let dst = p.destination_addr();

let protocol = p.protocol();

eprintln!(

"{} -> {} {}b of protocol {}",

src,

dst,

p.payload_len(),

protocol

);

},

Err(e) => {

eprintln!("ignoring weird packet {:?}", e);

}

}

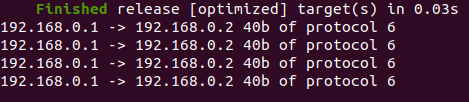

When we run the wrapper, we see a nicely formatted, more informational strings:

We can see that packets were sent to 192.168.0.2 from 192.168.0.1 with IP protocol 1, which is ICMP which is what ping uses. We can also use netcap to try and connect to the IP address (at any port) to see if it is reflected correctly:

We can see that 40 bytes are received of protocol 6, which is TCP.

This brings us to the end of the first 45 minutes of the tutorial. I will cover the rest of the tutorial in roughly one hour chunks, I think. Along with actually coding and ironing out issues, it takes me around an hour or so to get through 45 minutes of video, so it seems like a good duration. The tutorial is 13 hours in total, and I expect to complete it in a month or so. Ideally, I would like to finish it a lot sooner, but needs must, so 45 minutes at a time it will have to be.