An interesting infinite series

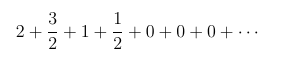

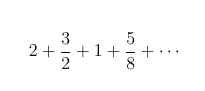

Published on 13 Jan 2025, under:An area of mathematics with which I had a lot of trouble was infinite sequences and series. To address this I have been practicing by solving a bunch of problems on this topic. Here’s an interesting, if somewhat simple, problem I came across -

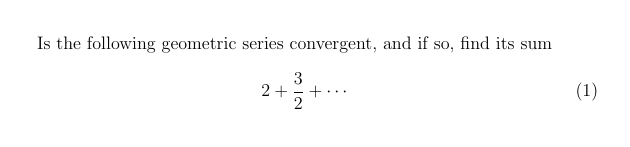

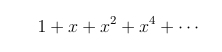

To recap, a geometric series is an infinite series of the form

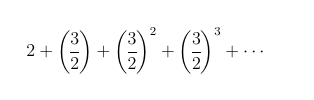

and if |x| < 1, the series converges, and the sum of the series is 1 / (1 - x). To get a better idea of (1), let us write out a few more terms of the series. As we are told that it is a geometric series, it seems reasonable to assume that the series looks like this

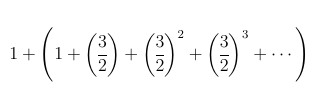

At first glance, series (1) does not really look a geometric series, as the first term is not 1. However, we could rewrite the series in the following fashion

This way, the series inside the parentheses is geometric, with x = 3/2. Since 3/2 > 1, we can conclude that this series does not converge, and hence the original series does not converge either. So that’s that. But what if we played around with the constraints a little bit? What if the series was not geometric? In that case, the first thing we have to do is figure out the structure of the new series. Since all every term of an infinite series has to be is a definite number, xn, for every positive number n, we have a lot of freedom in choosing how to build this series.[1] For example,

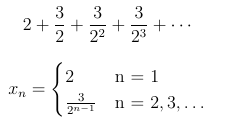

would be an infinite series that isn’t geometric. This is not very interesting however, since it is immediately clear that the series converges with a sum of 5. To make the job of constructing the series a little easier, let us insist that the nth term of the series, xn be expressable as some (hopefully simple) formula. So the following series

satisfies the requirement, but it’s not all that interesting (it’s almost geometric). The series converges with the sum coincidently also equal to 5.

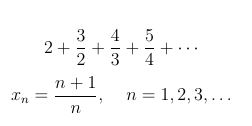

How about this one -

I like this one. The nth term is expressable as a simple formula, and it does not have any special cases, unlike the previous example. This series however does not converge. It gets an A-.

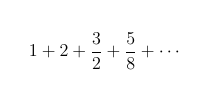

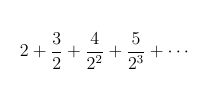

Let’s try one last series that could fit the first two terms of the series from the problem -

This series doesn’t look a lot like the one with which we started off. For one thing, the series progresses by increasing from one to two, and then decreases to 3/2 and decreases again to 5/8. Given that that last three terms are decreasing, we can get away with assuming that the rest of the terms in the series decrease too. In fact, if we re-arrange the series like this -

we can see that the give terms do all decrease. Now, by observing that we can write 1 as 4/4, 4 as 22, and that 8 as 23, the series becomes

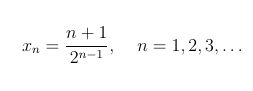

Now it is clear that

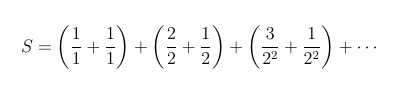

Here too, we have a nice simple formula without any special cases. As an added bonus, this series also converges (to see why, observe that the series of partial sums increases, the nth partial sum is bounded above, and an increasing series that is bounded always converges). To find the sum to which the series converges, we will let S represent the sum. Since xn = (n + 1) / 2n-1 = (n / 2n-1) + (1 / 2n-1), we have

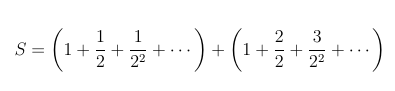

which we can be rearranged like so -

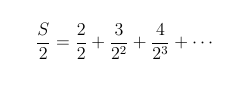

We are more or less done now, since the series in the first parentheses on the right hand side of the equation is the geometric series with sum 1 / (1 - 0.5) = 2, and as for the series on the second pair of parentheses, note that

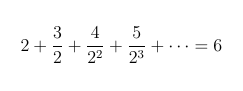

So we have S = 2 + (1 + S / 2) and solving for S gives us

[1] Calculus with Analytic Geometry, Simmons, George F., Chapter 13, pp 432, 439